Maddi Bacon: Illustrating Impact

All images courtesy of Maddi Bacon

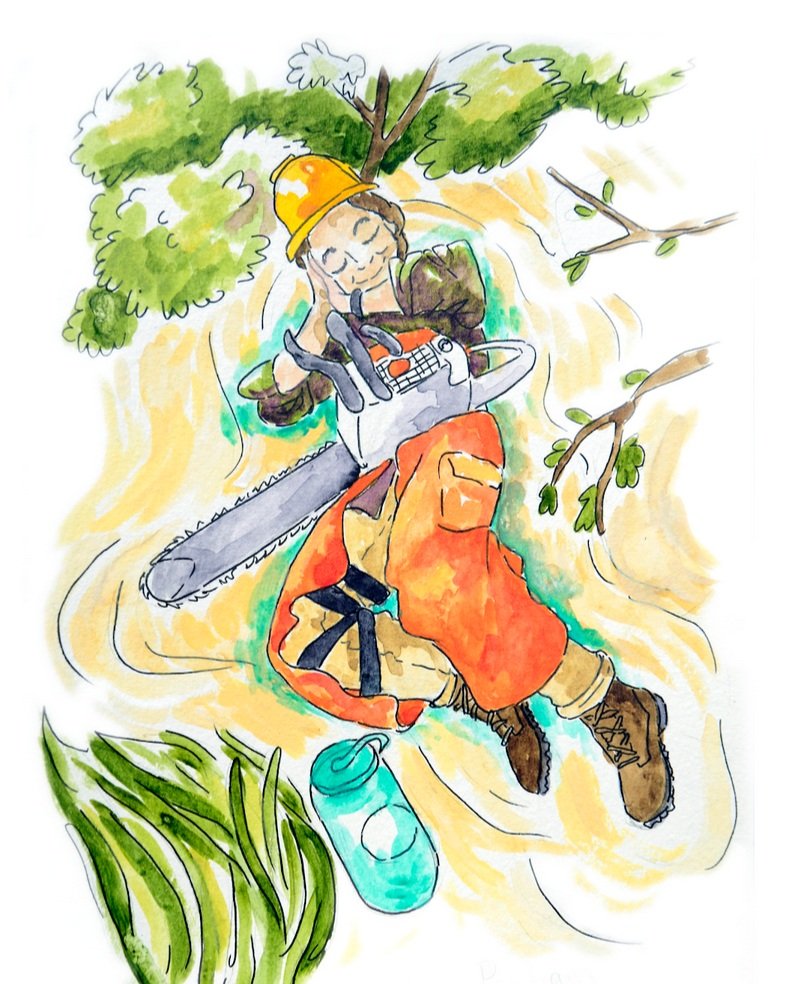

Trail work– and conservation work generally– can be a very visceral, emotional experience. It’s all at once dirty and exhausting, deeply fulfilling and rewarding. Unsurprisingly, conservation workers often find artful ways to express this mélange of feelings, like Victoria Vandervoort’s German Expressionism-inspired illustrations, or David Linares’ pop-art style imagery.

Artist and conservation worker Maddi Bacon (they/them) has focused their talents on a particular medium: the comic book. Comics are incredibly rich with artistic devices; they are visual but also textual, and the layout of the panels themselves can serve as a tool to evoke a certain feeling, pace, or emotion.

Maddi’s comics explore the nuanced and varied experiences of working in conservation in a way that is immediately relatable to people who have worked in the field, and illuminating to readers who have not. It’s not all sunshine and rainbows working in conservation, and Maddi’s work does not shy away from these realities. Rather, they probe, explore, and weigh the hardships, the beauty, and the beauty in the hardships of this particular field.

These aren’t superhero comics replete with onomatopoeic whiz bangs and ka-pows. But if you give them a read, you might learn something– or, more importantly, feel something– familiar or entirely new.

Joe Gibson: Tell me a little bit about your background. Where are you from? How did you get into trail work?

Maddi Bacon: Oh man, it’s sort of a crazy journey. I grew up on the east coast in Delaware and I went to school for Fine Art. The structure of college was really hard for me. Spending so much time inside and spending so much time alone working on projects. Near the end of my time at school I joined a community service club, and through them learned about AmeriCorps and Conservation Corps. After I graduated I applied to different art jobs and didn’t get any of them. So I decided that if I couldn’t get a “real” job I’d at least go on an adventure. I had never lived outside of Delaware before. So I applied for an AmeriCorps term with American Conservation Experience (ACE) and in 3 weeks I was planning my move to Flagstaff, AZ.

I had no idea really what to expect and I don’t know how anyone could have prepared me for the experience. I was living in a house with 30+ corps members, sharing a bedroom with 5 people, camping and doing physically demanding work for 8 days at a time, learning how to build trails, remove invasive species, build fences, and how to keep hiking when I’m tired. It was amazing. It was life changing. I was hooked. I’ve been doing seasonal work ever since.

JG: Where have you done trail work? With which organizations?

MB: My first experience was with American Conservation Experience (ACE). I did a 7-month term as a corps member in Flagstaff, AZ. That is where I’ve done most of my trail work and where I really fell in love with it. We did a lot of really cool rock work projects. I spent a month straight once on the Legends of the Superior Trail and built some crazy big staircases. After that I did a term as a crew leader for Northwest Youth Corps (NYC) and Montana Conservation Corps (MCC). In NYC I did a little bit of trailwork, but my term there was mostly doing a fence removal project and tree planting project. I really loved MCC and thought they were the most intentional and well-structured corps I had ever worked for. I also did a Student Conservation Association internship called Integrated Fire and Recreation Internship Program, which is where I got my red card and got into wildfire.

Excerpt from the zine “Notes from the Field,” featuring caption submitted by Andrew Connelly.

JG: How has your experience with trailwork informed or inspired your artwork?

MB: It’s more that, I think that trailwork and field work healed my relationship with my art practice at a time when I really needed it. At the end of my time in college I felt really uninspired. For four years, all I had done is pump out art projects for assignments. I didn’t really have time or energy to do other things because it was so time and energy consuming to make the projects and I also had to work a job. There came a point where I didn’t feel like I had anything to “make art about”. I had nothing else going on. At the same time I was starting to become disgusted by art practices (by others and myself). I was tired of seeing people make political art, or art about an issue such as homelessness or the environment, but then do nothing about that issue. It feels exploitative, to take these issues that have really large impacts on other people, and use them as trendy topics for your good grade or money with no intention to do anything that will actually affect the issue. I felt this sense of self disgust that I wasn’t doing anything that mattered or was direct action.

So that’s the mental state I was in when I signed onto my first trail experience with ACE. I wanted desperately to do work that would really make an impact in a real and tangible way. And trail work gave that to me. I was doing work on public lands, building trails so that people can recreate and care about the outdoors. I was also removing invasive species and building fences to keep cattle out of environments that they would be destructive to.

As a crew leader, not only was I doing the work, but I was also acting as a mentor who could teach others. It felt immensely impactful. All of the sudden, I had interesting things to make art about again. I have learned so many things from trail work and field work, about tools, the ecosystem, hard work, myself and my gender that make such intricate and interesting topics. On top of that, it takes some of the pressure off of me for my art to feel like it’s “changing the world”, because I am doing work that has an impact. The art can just exist as a way for me to reflect on my experiences and to show other people what I’ve learned.

“Notes from the Field” and “Conservation and Gender,” two zines by Maddi Bacon.

“I wanted desperately to do work that would really make an impact in a real and tangible way. And trail work gave that to me. It felt immensely impactful. All of the sudden, I had interesting things to make art about again. ”

Excerpt from “Notes from the Field,” featuring a story submitted by Kayla Johnson.

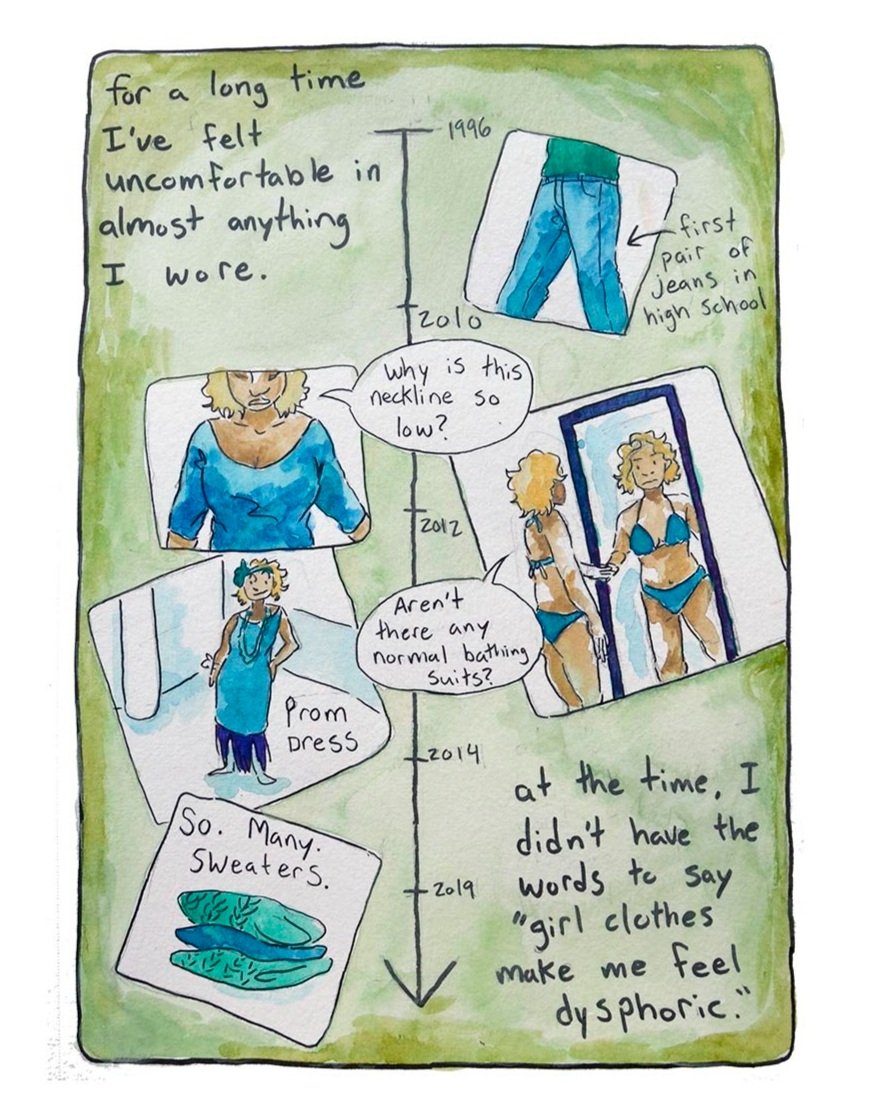

JG: You created a beautiful little comic called “Conservation and Gender” that uses clothing as a device to explore both the liberating and oppressive aspects of trails. I think it’s a story relatable to many non-binary folks and women in trailwork. Can you elaborate more about the tensions that exist between “work clothing” and gender?

MB: Conservation and Gender was me having all these mixed up thoughts in my head about gender and clothes and my experiences in conservation corps. For so much of my life I have really struggled with clothes. I don’t have a strong sense of “fashion” but I constantly felt like everything I wore felt “off”. Not just that I didn’t look good, but that I felt extremely uncomfortable in clothes that either were too constricting (jeans or stiff pants) or limited the way I could move because of how “revealing” they were (such as skirts that mean you have to keep your knees closed, or necklines that were very low and you’re constantly giving cleavage shots). For the most part, I was wearing the “girl” clothes I was supposed to, but even the times I was wearing “boy” clothes, I think I was upset that it still looked like a girl dressing up as a boy, and not that I suddenly had clothes that fit me and were comfortable.

I think joining a conservation corps finally started to put the pieces together in my head. We were camping and working for 8 days straight. I had bought myself these Carhartt overalls as work pants. And for those days we were working…. We were all dirty and nasty, our clothes didn’t serve any fashion or gender purposes. It was the first time where I felt relieved of that pressure for clothes to look any certain way. They just had to serve the purpose of being comfortable to work in. And, that sudden release of pressure to have to look like a girl felt like a missing clue to thoughts I’d been having my whole life.

When I was reflecting and thinking about all of this, I didn’t have all of the exact words - and I still don’t- to explain how I feel. So I turned to writing a comic. Comics allow me to be very precise and vague at the same time. Because I don’t have to write everything out like a book, I can lean into images and colors to evoke these emotions and moments. Stories are typically supposed to have these neat little narratives that build and have a climax and an ending that wraps it all up, but when I’m writing about myself I don’t always have that, because I’m a human and not a fictional story with an ending that makes sense. I keep going, and changing, and thinking new things. So my comics about myself can be somewhat rambly or have endings that don’t feel like a finished thought. I think that’s why I didn’t try to write too many definitive “labels” or conclusions into Conservation and Gender. It was meant to capture a time of reflection and thought, not a journey that had reached its completion.

JG: Your comic, “Mount Steel” is part of the Olympic National Park Terminus Project, which aims to use artwork to immortalize the disappearing glaciers of the park. How do you see comic books like Mount Steel as a medium for climate education and activism?

MB: This project was so fun to work on. I got to collaborate with scientists from Olympic National Park that had been doing glacier research for years. What was really interesting to me, as a person who works for public lands and is currently a biological science technician for a National Park, was the very human side of the story. I wanted to know what the glacier monitoring protocol was like, because I had done other monitoring protocols where I was the one out there collecting data, and it can be very hard work. I’ve done forest monitoring plots where we are hiking super far off trail, navigating by compass, climbing over fallen logs, and searching for one wooden stake that is hidden under ferns, or one tree tag that is the size of a quarter, and you get frustrated and exhausted and maybe you want to scream a little because the data from five years ago doesn’t match up with what you’re seeing now, and it’s all so that you can have this long term data set and hopefully understand the ecosystem a little better. And what would it feel like, to do that work, for years, to learn that the thing you are monitoring is going to disappear, and how do you even convince yourself to keep doing the work after that?

Bill Baccus is the physical scientist at Olympic, and I couldn’t have asked for a better scientist to collaborate with. He not only answered all of my science questions, but he had some really inspiring and insightful things to say about his glacier research. He admitted that yes, it was depressing, but having the data gave him a platform to spread awareness that he didn’t have before. The data creates a staggering picture of how climate change is permanently changing our landscape and ultimately will affect us.

So what I wanted so badly to do with my comic Mount Steel is to tell this story of science, how we as humans decide to value or not value things, and how you can take a story that ends with “and then they will all disappear forever” and find a way to be inspired and not just depressed. I think the power of comics as a medium for education or activism is that, at their core, comics are stories. The combination of images and text allows for a unique art form that can tackle complex and emotional topics. It allows for narratives to be told in ways they couldn’t exist in any other form. Complex environmental topics can be more easily explained with a combination of images and text. When you are looking to inspire dialogue and change, people are usually not motivated by simple facts and data points. They are inspired by stories and narratives that attach emotion to facts, or make concepts relatable to them.

“Notes from the Field” includes snapshots, interviews, and life lessons from your conservation corps experience. What about the conservation/trails world inspired you to share these stories?

Notes From the Field was actually a Covid creation. I had moved to Montana for my job with MCC and we had all just been furloughed for 5 weeks, with no idea what was going to happen with the pandemic or if we would actually get our jobs back in 5 weeks. I needed some sort of project to work on to keep sane and I was thinking about how lucky I have been to do so many cool jobs and how every time I try to explain my jobs to other people they’re always quite confused or don’t really grasp the magnitude of the experience. So I made a Google form just asking people to send me photos of themselves doing field work and a short little text blurb about it. I posted it on instagram, not really knowing what sort of responses I would get, and was amazed that I actually had so many strangers find the post and submit. I was very specific that I didn’t want photos or stories of people recreating, but that it had to be field work, because I’m interested in showing the “wild” and “outdoors” as a place that isn’t divided from humanity, but as a place that has been stewarded by humans for generations, and how beautiful and lively that connection to land makes us humans feel.

Excerpt from “Notes from the Field.” Artwork by Maddi Bacon, based on reference photos from Koa Dynes.

JG: Can you walk me through your process of creating a comic or illustration from ideation to completion?

Gosh, I could try but it hardly makes any sense to me either, so good luck.

Usually I have an idea bouncing around in my head for a long time, and I’ll ask myself “okay, but where are we going with this? What are you trying to say?” And If I can sort of figure that out I’ll write a script first, where I’m figuring out what the story is, what the text is going to be, and maybe plan some of the images.

The writing phase is probably the hardest for me. I’ll have a thought like “that time I was on a women’s crew and I was watching them hike down the hill alone with barbed wire felt like it meant something” but I don’t know what kind of story that is, just that I have strong emotions associated with it, and then months later someone is telling me about the Grand Canyon river patrol being disbanded because of rampant sexual harassment and I’ll think “That’s it. The story is how different my experience was to stuff like that” which is how I cobbled together the narrative of my comic, Articulate the Difference.

Once I have a script written, I’ll do thumbnails, where I’m just doing really small sketches to feel out the pacing and images, deciding how I want it to look. And then I’ll dive into the real fun part, drawing and painting the pages. I use mostly ink and watercolor, but lately I’ve been really getting into markers. Once it’s all finished I photograph it.

Reference photo and artistic rendering from “Articulate the Difference.”

JG: Where can people see and purchase your art?

MB: People can follow me on Instagram @baconbitmadison or they can visit my website.

You can purchase my comics and zines either on Amazon or Gumroad

JG: What are you currently up to? Art full time? Trails? Something else?

MB: Right now I’m working as a seasonal Biological Science Technician at Lewis and Clark National Historical Park! I love it here. I’ve been able to learn about so many things- for example did you know that dragonflies live as larvae for five years before they transform into dragonflies?!

It’s a small park, so I get to do a wide variety of work, such as forest monitoring, elk monitoring, and eDNA sampling. And I’m always thinking of new comics to write! This fall I actually have another artist residency lined up with Playa at Summer Lake. A cohort of artists will be going there to learn about water and wildfire specific to that region and we’ll have until April to make art pieces for a show. So I’m really excited to jump into another experience of working with scientists and conservationists to learn about the ecosystem and write about it.

Maddi collecting field data as a Biological Science Technician.